Deictic Color

I recently read Ecumenicism, comparability, and color, or: How to have your cake and eat it, too

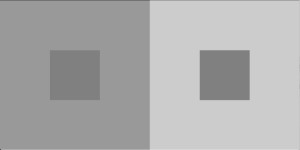

by Jonathan Cohen. The situation he discussed is based on the classic color perception experiment in which a gray square surrounded by a lighter color is perceived as being darker than the same square when surrounded by a darker color (image based on R code obtained here)

Cohen argues the position that the color of the square within the darker square being lighter and the square within the lighter square being darker were both true. Although I found the arguments persuasive, as far as they went, something seemed off. I found it too concerned with the perceiver as trying to achieve some internal color reference rather that trying to perceive a deictic reference that could be conveyed to a co-observer.

The direction of the argument reminded me of the whole issue of pragmatically matching and rendering colors, rather than that of calibrating our color estimates.

Now, in fairness, Cohen’s relationism addresses all the issues I discuss here, but with fewer empirical tethers. Color is hard — it’s hard to reference/designate a color and hard to show/display a color. In this way it is similar to situations in which we attempt to develop analytic solutions rather than functional (or situated) ones. A classic example being: “What makes something a chair?”

Matching a color: what color is it?

The Pantone mailing list recently had an interesting video about Tiffany Blue and how difficult it is to make/match etc.. This difficulty is partly by design, but also because matching is a hard problem. In general, swatches (and material specific swatches), are the norm (see this Pantone page on some of the issues addressed and the products entailed ). There are many reasons for this: swatches are inexpensive; they can be accurately produced at central, controlled facilities (assuring consistency); and they’re portable — they can easily be put in a pocket and transported to the relevant spot to serve as a reference under the very lighting and environmental conditions that are of import. (N.B. this is just for matching. As we call know the “feel”/qualia of a color varies greatly depending upon it’s scale, e.g., being in a red room feels much different from being in a while room with a red teacup. This, at least partly, is because the reflectance from the walls of a red room shifts the hue of everything else in the room).

In addition to lighting, issues surface finish and material (especially materials with texture or translucency also have important impacts upon the perception of the color — which is part of why Pantone will give you a textile swatch of your color).

Matching a color, then, consists of putting a color on an object in such a way that its perceived color will not be discernibly different from a color swatch of a “similar” material placed next to it.

This is disjoint from the goal of producing a display that can show colored objects next to each other in a way that is (to borrow a phrase from Cohen) ‘coarse-grained’ accurate. e.g., under no circumstances does your non GMO lawn look pink while the dirt next to it looks brown.

Producing a Color

When it comes to the production side of color. That is, displaying something that will be perceived as a “particular color” implies, at a minimum, that it is displayed in a way that its relationships to adjacent colors is not skewed too badly. These issues are exacerbated because no current displays can reproduce the full range of colors — whatever your priori definition of “real color” is, you won’t be able to achieve it, and compromises are necessary. In addition to these concerns about the color of a given pixel, we also may want to adjust our display depending upon the environment we will be displaying the color in.

Take a simple example: a white sheet of paper. The first question would be which paper, for there are many. The second question is in what environment do we wish to represent it? Even if we were to assume that white is just a perfect selector of the oncoming light, that would still mean that it’s color would be that of the light source. Therefore, the color shown for our sheet of Hammermill white on the display would be different if the light source was a sun, a fluorescent tube or a candle, and of course, these choices would inevitably impact our ability to distinguish adjacent colors (as anyone can attest who has tried to distinguish colors lit by a sodium vapor lamp).

Deictic Color

Given these interactions between eyes, environment, material type and reflectance, in addition to color, it seems unsurprising that our references are tuned to picking out local variations when speaking about color. Speaking is the paradigmatic act of conveying information to someone in our shared environment — since we can’t see the environment with the other person’s eyes the best way to pick out something in the environment would be by referencing the local variations in the scene.

A reference to the dark square in the lighter one or the light square in the darker one allows the listener to easily pick out the referenced object and would remain robust in the face of any local variations in lighting conditions etc.

Again, I think that these concerns are adequately addressed in Cohen’s framework and that his Coarse Color concept is a good solution to “moderately stable interpersonal color references”. I just felt that there was an inflated set of expectations about our abilities to achieve accurate color perception — there is even less reason to think that our perception of color is metrically accurate than to think that our untrained ability to visually measure size.

Leave a Reply