There’s Something Out There — Two Books About Knowledge Of The World

I want to consider two books that address knowing things in the world

Tyler Burge’s Origins of Objectivity and Andy Clark’s Surfing Uncertainty

Although they are both books by philosophers and deal with similar topics, it would be difficult to imagine them being any more different. Burge’s brief is backward looking — how would the work of previous philosophers be different/improved if they had access to current cognitive science data (The book also argues that contemporary philosophers too often ignore the data being generated by cognitive science). Clark’s book, on the other hand, is more forward looking — integrating current data and models, identifying their areas of strength, topics that need further investigation, etc..

Interestingly, Burge doesn’t cite any of Clark’s work and Clark only makes one cursory (“the impact of figure-ground convexity cues in depth perception”) citation of Burge’s (Origins of Objectivity). I understand it at one level, since their goals are different, but I still find it surprising.

Surfing Uncertainty

The core of this book is prediction: the way in which we come to understand our environment, and validate and refine that understanding is by constantly, continually, predicting it and constantly, continually, testing those predictions against our perceptions.

It’s this incessant, fine-grained testing that provides us with assurance that our perceptions reflect an accurate (or, at worst, phenomenally consistent) view of our environment.

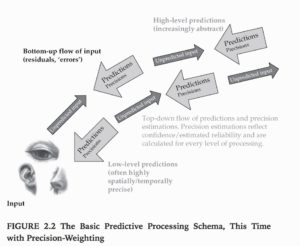

The “basic” model is one of constant flows between lower and higher levels of processing: lower levels evaluation the situation they are presented with vis a vis the current prediction and propagate errors up, each layer also pushes its best current predictions down to the layer below it.

Errors propagate up, predictions propagate down, constantly tested, constantly updated. The information passing between levels is “level appropriate” and processed. In this model the “raw sensor” data isn’t a core consideration.

The book consists of an extensive, thoughtful review and synthesis of the literature in the area with good detail on the issues and findings.

Three areas I wanted to highlight

Illusions ~= heuristics in the face of environmental underspecification It’s well known that the information available to our senses from the environment at any particular location isn’t enough to unambiguously specify what is present in the environment. What we perceive is a best guess as to what’s in the environment given the available data. Best Guess in this case means the one that is the best statistical fit with this data given what we’ve seen before and our estimates as to the accuracy of the data.

Accuracy weighting: the errors and predictions from each layer are weighted by the best current estimate of its accuracy. The accuracy reflects its consistency, both local (local being within the local space of that sensory modality) and global (global being within modality and cross modality).

Multi modal: As mentioned above, consistency across senses is a factor as is our expectation of what we expect to see, e.g., if we come home and our computers are missing; if there’s a strange smell, etc. it will trigger agent activity on the part of our other senses and of our actions.

This cycle of probabilistic matching of top down prediction and bottom up perception has some interesting knock on effects. For example: yes, the top down prediction of the experience is tuned to match what you’re perceiving, but what happens when you want to change to environment to match your goals, e.g., move your hand

A couple relevant quotes from section 7.7 Tickling Redux are relevant

Movement ensues, if that story is correct, when the sensory (proprioceptive) consequences of an action are strongly predicted. Since those consequences (specified as a temporal trajectory of proprioceptive sensations) are not yet actual, prediction error occurs, which is then quashed by the unfolding of the action.

And

But notice that movement will only occur if the body alters in line with the proprioceptive predictions rather than allowing the brain to alter its predictions to conform to the current proprioceptive state (which might signal e.g that the arm is currently resting on the table).

So there’s a balancing act between bottom up promulgation of information gleaned from what’s being presented, and top down promulgation of information about expectations. (Now it’s important to realize that the feedback signal from environment through our various environmental understanding systems are differential, meaning that it’s only the mismatch between the environment and the processed stimuli — if there’s a match, “no signal” is transmitted)

What I take these two quotes to mean is that movement would normally be quashed by this system since it would update the expectation to match the perceived. However, if the error signals are quashed, the expectations will not be updated and “reflex arc movement” will occur and motion will ensue.

I’ve spent a while trying to wrap my head around this, and decided that it was easiest to think of it as wrapping my hand around it.

If we’re exploring an object by touch, e.g., how sharp is that knife edge? We brush our finger across it, getting feedback and estimating the sharpness. Top down willful motion of the hand is performed in pursuit of getting bottom up information from the passive “edge matching” movements of the finger.

In contrast, grip the hammer. Willful motion all the way down, but lots of reflex arcs pretty quickly. We don’t will how to get the right grip, we just want one, and the hand finds it. If we’ve just put the hammer down and have a physical memory of its location and positioning, I could easily see it being reflex arc from the point of the hammer the nail thought on down.

Origins of Objectivity

The goal of this book is addressing the shortcomings of the work of previous philosophers, in light of the current findings of cognitive science. The bulk of the book is taken up by a detailed analysis of this impact.

“A persistent theme in the book is that philosophers repeatedly made claims about empirical representation without knowing much about perception—more particularly, without reflecting on scientific work on perception.”

One important thing to note upfront: Objectivity as used here means to ascertain something in the world that exists independently of oneself. It does not, by any means, indicate 100% in accordance with ground truth (in contrast to my usual sense of objective), Burge’s view has ample room in this view for uncertainty and error.

The terminology that Burge uses for his approach is anti-individualism. It’s an interesting, and well considered, term:

“This thesis is known as anti-individualism. Anti-individualism is the claim that many mental kinds constitutively depend on relations between individuals and a wider environment or subject matter.”

Standing in stark contrast to the burdens placed upon individuals in more conventional schemes

“The individual’s being embedded in an environment and bearing non-representational relations to it do much of the work that was supposed to be done by supplementary representational capacities under the individual’s control.”

This contrasting approach is what I’d call this the propositional logic view: to achieve true knowledge you’re required to ground out (ground, in this sense, being ~= ground truth) all your assumptions. I think the difficulty we’ve had in determining what all these assumptions are, despite at least a century of trying, speaks volumes to the likelihood of all 7,000,000,000 of us doing this on a daily basis.

This is very much in line with Clark’s assumptions:

- Things exist outside of ourselves in the environment.

- We interact with them.

- Others interact with them.

- We can perceive others interacting with them.

- In general, our observations of the interactions that others have with things in the environment match our own experiences and expectation.

- The ways in which we observe these things and interact with them does not abide by the expectations of a First Order Predicate Calculus (FOPC) approach, but rather has a (in Burge’s terms non-representational) basis in preconscious processing.

Accepting these premises allows one to be open to the idea that Objectivity is a capability that is available outside of the human species. The counterargument was never that animals, etc. didn’t perceive the world, but rather than they don’t have an understanding of objects per se., since understanding objects requires conscious thought. Remove the requirement for conscious thought, and the “human” restriction falls away.

All of this accurately tracks the best current understanding supported by empirical data.

The book continues with an explanation of Anti-Individualism, as with Objectivity the term is sensible, if a bit misleading. In this case Anti-Individualism doesn’t imply multiple individuals, but rather something beyond, and outside of the individual. This reinforces the multi species argument for Objectivity, since coordination between individuals acting upon objects in the environment is commonplace in “nature”.

Following this are two major sections: the first covering the work of prior philosophers; the second covering the science in greater detail. I concentrated on the philosopher part since I was already moderately well acquainted with this from my previous reading.

I felt that the section dealing with prior work were a bit of a mixed bag. At one level it is fair, and deeply important, to point out examples of severe misunderstandings in prior work. On the other hand, these flaws are built in to this work from the moment of conception, given their underlying lack of realism about the level of detailed predication required to support their analyses: the complete grounding of all our assumptions in FOPC form, represented a naive and idealistic undertaking, at best. As Burge points out, this stems from Descartes and Plato before him and was a continual source of problems,

Personally I find it difficult to divorce this desire of the ancients from their underlying need to distance themselves from animals and posit entities such as an immortal soul. Obviously, beings with immortal souls couldn’t rely upon being embodied for their basic operation, so the development of a “non embodied” mechanism became paramount.

Since we currently seem more comfortable delineating a divide between us and other species that is less sharp than previously assumed, we don’t have the need to develop frameworks that can support disembodied existence

Beyond that, I found his method of addressing each philosopher separately didn’t speak to me. I’m more of a structuralist: I’d have preferred that he proceed with the salient parts of the non-Individualist approach and map that into the concerns of each philosopher, rather than go bottom up independently for each philosopher. Since each person has a different set of concerns, this made for a treatment that was both lengthy and a bit disjointed. Also, since each philosopher was dealt with individually, it seemed that the issues of concern to this book were sometimes overrated as being major concerns to the philosophers covered.

Summary

Two very different books, covering roughly similar ideas in radically different ways.

Burge’s Origins of Objects is a consolidation what we know, and look back to prior ideas to see how they have been disproven and would need to be changed to reflect our new understandings.

Clark’s Surfing Uncertainty consolidates and integrate what we know and use it to examine in detail how we as embodied statistical inducers op. It’s an exciting read.

Leave a Reply